This is an excerpt from the economic discussion document launched by MEP Matt Carthy on October 27, entitled The Future of the Eurozone. Download the full document for a referenced version of Chapter One, below.

BACK IN 1929 when the Wall Street crash hit, the response of then-US President Herbert Hoover was to restrict government spending – an action now almost universally acknowledged as having turned the stock market crash into the Great Depression.

The free-market ideology underpinning Hoover’s austerity policies held that an economy with high unemployment could return to full employment through market forces alone. Instead of boosting public spending, the government should do the reverse. By cutting government spending and increasing taxes, the government deficit would be reduced, which would restore market “confidence”. This restoration of confidence would lead to increased private investment, and the market would adjust itself to return to full employment.

The confidence fairy

The confidence theory was demonstrated back in 1929 to be incredibly damaging and to achieve precisely the opposite effect of what it aimed to achieve. The actual effect of implementing austerity in a period of economic downturn was to cause a contraction in the economy, thus weakening the economy further, causing tax revenues and national income to fall, and the deficit to increase. The contractionary impact of austerity policies during a downturn was explained by John Maynard Keynes during the 1930s, and Keynesian models have proved to be a reliable predictor of growth (or lack thereof) in the wake of the 2007-2008 crisis.

Countless books, academic studies and articles have outlined how the programmes imposed by the Troika – the European Commission, the European Central Bank (ECB) and the International Monetary Fund (IMF) – on the Eurozone’s “peripheral” economies since 2008 have exacerbated the crisis. In the decades before the global financial crisis, these same policies had caused the exact same devastating contractionary effects when imposed under the guise of “structural adjustment programs” by the IMF across Africa, Asia and Latin America.

But while Keynesianism was experiencing an academic and policy revival internationally following the global financial crisis, Europeans somehow managed to cling to the confidence theory, which persisted in the decades beyond the Great Depression to this day. It is the dominant theory that has shaped both the structure of the Eurozone and European Union (EU), and the EU response to the global financial crisis of 2008.

In 2011 at the height of the Eurozone crisis, Nobel Prize-winning economist Paul Krugman memorably dismissed this theory as the “confidence fairy”. Two years later, commenting on the theory’s persistence in the face of overwhelming evidence to the contrary, he added: “European leaders seem determined to learn nothing, which makes this more than a tragedy; it’s an outrage.” Fellow Nobel Prize-winning economist Joseph Stiglitz has dubbed the free-market fundamentalists’ obsession with reducing deficits as “deficit fetishism”, pointing out that “no serious macroeconomic model, not even those employed by the most neoliberal central banks, embraces this theory in the models they use to predict GDP”.

Europe’s lost decade

It is common for scholars to refer to the results of the IMF structural adjustment programmes from the 1970s-1990s in Latin America, Asia and Africa as having caused these continents “a lost decade” or “lost decades”. Europe has lost a decade but there is a danger that it may lose several more – not only because of the policy responses to the crisis but because of the actual structure of the Eurozone. The results of the European response to the crisis are damning. Three patterns are obvious: the Eurozone countries have in general fared far worse in terms in terms of recovery than countries outside of the common currency; the recovery within the Eurozone has been sharply asymmetrical, with divergence between strong and weak countries increasing; and there has been a significant rise in inequality across Europe.

Growth in the US and Britain has been weak since the crisis but it has far outpaced the Eurozone recovery. It is difficult to even use the word “recovery” to describe the Eurozone experience – only last year did Eurozone GDP reach its pre-crisis level. In June 2016, the Eurozone unemployment rate was still in the double figures at 10.1 per cent; while the EU-28 had unemployment of 7.7 per cent. But the unemployment figures in several of the crisis countries remains double the Eurozone average – in Greece by 2017 the unemployment rate was 21.7 per cent while at the same time in Spain the jobless rate was 17.8 per cent. The figures are masked by the huge levels of emigration that the crisis countries experienced as well as the fact that number of hours worked per worker has declined across the Eurozone.

Stiglitz notes that youth unemployment persists at twice the level of overall unemployment. “The persistence of high unemployment among youth will have long-lasting effects – these young people will never achieve the incomes they would have if job prospects had been better upon graduation from school.”

While the Eurozone stagnated for a full decade following 2007, countries within the EU but outside the Eurozone had a GDP 8.1 per cent higher than in 2007 by 2015. The United States had a GDP almost 10 per cent higher in 2015 than in 2007. Over the same period, the Eurozone’s GDP grew by just 0.6 per cent.

When measuring living standards it is more accurate to examine GDP per capita than GDP overall, and while in the US GDP per capita increased by more than 3 per cent from 2007-2015, while over the same period in the Eurozone it actually declined by 1.8 per cent. As living standards have declined – devastatingly in crisis countries, and especially in Greece – income inequality has also risen drastically. In its Economic Forecast last autumn, the European Commission warned of a potential “vicious circle” as expectations of long-term low growth affect investment decisions, and that “the projected pace of GDP growth may not be sufficient to prevent the cyclical impact of the crisis from becoming permanent”.

The declining level of growth in the British economy since the Brexit vote means a “strong downward revision of euro area foreign demand”, while the “sizeable depreciation of sterling vis-à-vis the euro is expected to have an adverse direct impact on euro area exports to the UK”. Eurozone exports were forecast to decrease slightly this year and stagnate in 2018, while possible financial crashes in China or the US and the ongoing non-performing loan banking crisis in the Eurozone pose serious risks.

Despite these sober warnings, European leaders and the financial press have raucously celebrated the anemic growth in the Eurozone’s GDP in the first two quarters of this year, of 0.5 per cent and 0.6 per cent respectively – crucially, driven by a slow increase in domestic demand as opposed to export-led growth. But this celebration ignores the fact that in normal circumstances, these figures would be viewed as abysmal, and that global economic forces pose serious threats to this fragile recovery.

Fairies and leprechauns

Predictably, these feeble shoots of growth are described as being the result of austerity policies by those who have claimed for the past 10 years that austerity will start to work any day now. A slightly recalibrated confidence theory has been proposed by a small number of economists associated with the neoliberal school of thought since the 2008 crisis – that of an “expansionary fiscal contraction”, with Harvard’s Alberto Alesina and Goldman Sachs’s Silvia Ardagna leading the charge with their joint paper in 2009. What they are actually recommending largely amounts to recovery through beggar-thy-neighbour competitive devaluations (or in the common currency, internal devaluation).

Stiglitz points out that these instances of economic recovery are actually cases where certain countries had “extraordinarily good luck” in that “just as they cut back on government spending, their neighbours started going through a boom, so increased exports to their neighbours more than filled the vacuum left by reduced government spending”. Several papers from the IMF itself have backed up this analysis.

This is largely what happened in the Irish economic recovery, which has become the EU’s poster child for austerity policies. The narrative goes that the Irish state followed the German model – it followed all of the EU rules and implemented the Troika’s structural reforms, slashed government spending to reduce the deficit, cut wages to increase competitiveness, and as a result restored market confidence, depressed domestic consumption and experienced a corresponding rise in exports.

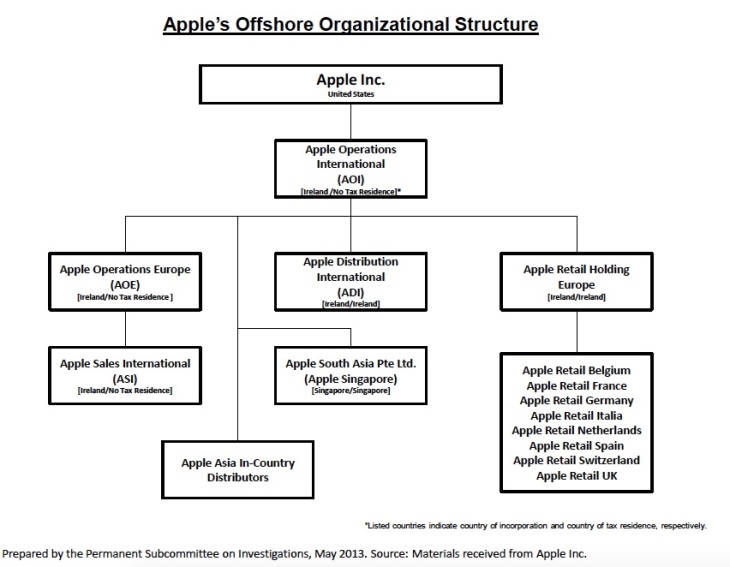

The reality is more complex, and is based on a combination of growth in jobs in the indigenous sector, including the services sector, arising from favourable exchange rates for the Irish state; and on the illusory “growth” of GDP caused by the industrial-scale corporate tax avoidance strategies undertaken by US multinationals in the technology, pharmaceutical and aircraft-leasing sectors.

There has also been a certain level of export-led growth since 2009 but it has been hugely exaggerated and difficult to reliably quantify. But this export-led growth did not in any way fit into the German model and “expansionary austerity” narrative of an internal devaluation based on lowering wages and domestic demand. Rather than being based on manufactured exports with a competitive edge because of wage cuts, export growth took place among firms in high-wage service sectors such as technology and finance during a period in which wages in these sectors were going up.

Of course, last year’s ludicrous announcement that Irish GDP had grown by more than 26 per cent in 2015 raised an enormous red flag that all may not be what it seems in Ireland’s economic recovery. Krugman, coiner of the “confidence fairy” term, found another apt folkloric description for the occasion: “leprechaun economics”.

These figures were so detached from reality that they were cause for serious alarm but, incredibly, the Irish government welcomed them. According to the figures, per capita income apparently rose to 130,000 in 2015, and the state’s industrial base doubled in just one year. But the Net National Income grew by 6.5 per cent in 2015 while consumer spending rose by 4.5 per cent. These income and consumption figures are a far more accurate reflection of real economic activity and growth. Official GDP figures have a major and serious role to play in fiscal planning, spending and borrowing. They need to be credible and a measurement of real economic activity.

Most alarmingly, the figures reveal a glimpse at the level of dubious accountancy tricks being played by multinationals in Ireland during a period in which the Irish government claimed it was committed to playing its part in the global crackdown on tax avoidance. The Irish Central Statistics Office (CSO) identified relocations and inversions by multinational enterprises as the major contributing factors to the so-called growth. It seems as though there was a rush by multinationals to ‘turn Irish’ in 2015 in the context of global action on tax avoidance and tax havens, through inversions – where a multinational corporation changes tax domicile after it buys up a smaller Irish-registered company. The transfer of financial assets and intellectual property patents into Ireland does nothing to actually create jobs or contribute to growth in the real economy.

In response to the fantasy figures for 2015, the Central Bank of Ireland published a study stating that to measure growth or activity without the reality being skewed by the activities of multinationals, GNI* (Gross National Income, modified) should be used instead. GDP and Gross National Income differ as a result of the “net factor income from abroad” (eg, repatriated profits and dividends of multinationals). While GDP is a measurement of the income generated by the economy, GNI measures the income actually available to its residents. Irish GDP is more than 20 per cent greater than GNI, one of the largest differences among all economies globally (the two figures can usually be used interchangeably).

But even using GNI is not sufficient to get an accurate picture of real economic activity according to the CSO, which developed a measure of “modified gross national income” or GNI*. GNI* is Gross National Income “adjusted for retained earnings of re-domiciled firms and depreciation on foreign-owned domestic capital assets” – ie, modified to account for depreciation on intellectual property owned by technology and pharmaceutical firms. When GNI* is used to measure the Irish economic recovery, the picture is not so rosy. “The Irish economy is about a third smaller than expected. The country’s current account surplus is actually a deficit. And its debt level is at least a quarter higher than taxpayers have been led to believe,” the Financial Times reported on the first set of “de-globalised” data on the Irish economy in July this year.

For 2016, the value of the Irish economy according to its GDP was €275 billion, but according to its GNI* its value was €190 billion – a huge difference that indicates that not only is the Irish economy not nearly as strong as the official narrative portrays, but also that the Irish state may have facilitated multinationals in avoiding up to €85 billion in tax in one year alone. The CSO reported that in 2015, government debt was 79 per cent of GDP but 100 per cent of GNI*; and that while the state’s fiscal deficit was 1.9 per cent of GDP, it was 3.4 per cent of GNI*, well above the 3 per cent limit imposed by the EU’s fiscal rules.

There has also been growth in employment over the past three years in the Irish indigenous sector. For example, job growth took place in the agriculture and food sectors, and in accommodation and tourism. This growth was based on two related factors. The first was the depreciation of the euro against the dollar and sterling as a result of the crisis, and the second was the relatively higher economic growth in Britain and the US, the Irish state’s two largest trading partners. The (temporary) lower value of the euro was critical to the recovery experienced in the Irish indigenous sector. The relative growth in the US and Britain was also influenced by the fact that these two states are not constrained by the Fiscal Compact rules – borrowing in the US and Britain did not fall below 3 per cent since 2008.

But the specific circumstances of the Irish state’s trading patterns mean that this “recovery” cannot be transposed or replicated in other member states of the EU. It also poses significant risks, especially the risk of a significant fall in the value of sterling as a consequence of Brexit. A sharp depreciation of sterling against the euro – something we are already beginning to see – would likely jettison this recovery. Worrying signs of a technology bubble, a new Irish housing bubble and a massive shadow banking sector are all factors that may also influence this recovery. Crucially, the structure of the Eurozone itself, and the austerity ideology it has enshrined, make another economic slump inevitable.

The evidence shows that the Irish recovery happened in spite of, not because of, the EU austerity recipe – and it would have happened sooner, and with far less pain to the Irish people, had ideologically driven deficit fetishism been rejected.

A fiscal straitjacket

In 1992 the member states of the European Economic Community (EEC) signed up to the Maastricht Treaty, which laid the foundation for the common currency. The Maastricht Treaty enshrined the so-called convergence criteria – a set of rules members and potential members of the common currency were obliged to follow. To join the Economic and Monetary Union (EMU), states had to pledge to control inflation, and government debt and deficits, and commit to exchange rate stability and the convergence of interest rates. The blanket, one-size-fits-all fiscal rules in the criteria – that member states must keep public debt limited to 60 per cent of GDP and annual deficits to below 3 per cent of GDP – were proposed by Germany, based on its national Stability and Growth Pact.

The convergence criteria, as the term suggests, were aimed at achieving convergence among the diverse economies that were to form the Eurozone. The founders of the euro acknowledged the tendency for economic shocks to hit diverse economies asymmetrically in a monetary union. Without convergence, a common currency won’t work – for example, with diverse economies the interest rate set by the ECB for the entire Eurozone may impact positively on one country but negatively on another country with different economic characteristics. Without convergence, it would be difficult if not impossible to ensure full employment and current account (external) balance among different economies at the same time.

There are many spillover effects that one economy can have on another in a monetary union – for example trade imbalances and internal devaluations – but the only one that the Maastricht Treaty focused on was members’ fiscal policy. “Somehow they seemed to believe that, in the absence of excessive government deficits and debts, these disparities would miraculously not arise and there would be growth and stability throughout the Eurozone; somehow they believed that trade imbalances would not be a problem so long as there were not government imbalances,” Stiglitz comments.

Governments facing an economic downturn have three main ways they can aim to restore the economy to full employment: to stimulate exports by devaluing their currency; to stimulate private investment and consumption by lowering interest rates; or to use tax-and-spending policies – increase spending or lower taxes. Membership of the Eurozone automatically rules out using the first two mechanisms, and the fiscal rules largely remove the third option from governments.

(The confidence fairy is almost always accompanied by a fervent belief in “monetarism” among neoliberals – ie, that only monetary policy by an independent central bank should play any role in economic adjustment, and anything else would amount to dreaded government intervention in the economy.)

When a Eurozone member state experienced a downturn, its deficit would inevitably rise as a result of lower tax revenue and higher expenditure on social security. But when the convergence criteria kicked in, causing governments to cut spending or raise taxes, it would invariably worsen the downturn by dampening demand. Moreover, debt and deficits did not, and do not, cause economic crises. Ireland and Spain were running surpluses when they experienced a crisis, and both had low public debt.

The convergence criteria are purely ideological and economically unsound. But as the European Central Bank (ECB) was preparing to begin operating to control inflation and interest rates, Germany pushed for the adoption of an EU-wide Stability and Growth Pact in 1997, including non-Eurozone members, to enshrine the fiscal control aspects of Maastricht, and more generally to increase EU surveillance and control over member states’ national budgets.

The Stability and Growth Pact has been called a lot of names in its day – the “Stupidity Pact”, a “Suicide Pact”, the “Instability Pact”, and more. And it is deserving of each one. In 2002, then-President of the European Commission Romano Prodi told reporters the pact was “stupid”, while French Commissioner Pascal Lamy called it “crude and medieval”. In practice, the Stability and Growth Pact has proved to achieve the opposite effects it claims to aim for. Cuts to government spending have a contractionary effect and cause the economy to shrink; when the national income shrinks, spending on unemployment benefits have to rise, and the situation gets worse. This is exactly what happened in the aftermath of the recessions in Ireland, Spain, Greece and Portugal.

Early in the 2000s, both Germany and France repeatedly breached the fiscal rules. But they were not penalised, and were always provided with an extension to try to meet the targets. Almost all EU member states have breached the rules at some point – during the recession only Luxembourg did not go over the 3 per cent deficit target. Fiscal contraction will exacerbate unemployment, but it may eventually restore a current external account balance – when demand for imports becomes so low as a result of the recession that exports catch up.

University of London Professor George Irvin has described German Chancellor Angela Merkel’s insistence that government profligacy is at the root of the Eurozone crisis as betraying “near-total ignorance of how economies work”. “Budget balance for a national economy is fundamentally different from that of the household or the firm. Why? Because budgetary (or fiscal) balance is one of three interconnected savings balances for the national economy. The other two fundamental economic balances are the current external account balance… and the private sector savings-investment balance. If any one account is out of balance, an equal and opposite imbalance must exist for one or both of the remaining accounts,” he wrote.

But despite the vast evidence that the Stability and Growth Pact was counterproductive and unenforceable, Germany pushed for the fiscal rules to be tightened yet again in 2012 through the Fiscal Compact Treaty, which created the obligation for the convergence criteria targets to be inserted into the national law of the ratifying states.

The Fiscal Compact

In 2010, Germany proposed the reform of the Stability and Growth Pact to make it stricter, and “in return” pledged to support the creation of a Eurozone bailout fund that member states could draw upon if they were in dire straits – with strict fiscal conditions attached, of course. The reforms aimed at enforcing compliance of the Stability and Growth Pact known as the “Six-Pack” and “Two-Pack” of additional regulations and directives were adopted at EU level.

In 2012, an intergovernmental treaty – the Treaty on Stability, Coordination and Growth – was signed by all EU Member States with the exception of Britain and the Czech Republic. (When Croatia joined the EU in 2013, it declined to sign.) The Treaty, known as the Fiscal Compact, incorporated the Stability and Growth Pact, the Six-Pack and Two-Pack requirements, and more. Its central principle is that member states’ budgets must be in balance or in surplus, which the Treaty defines as not exceeding 3 per cent of GDP.

Critics of the Stability and Growth Pact had called on the EU to focus not on the general deficit but rather the structural deficit – what the deficit would be if the economy were at full employment. But instead of dropping the general deficit limit, the Fiscal Compact has adopted rules on both the general deficit and the structural deficit. The structural deficit limits are set by the Commission on a country-by-country basis and must not exceed 0.5 per cent of GDP for states with debt-to-GDP ratios of more than the 60 per cent limit, and must not exceed one per cent of GDP for states within the debt levels.

The “debt-brake” rule is the convergence criteria rule that government debt cannot exceed 60 per cent of GDP. The Fiscal Compact enshrines the rule that members in excess of this limit are obliged to reduce their debt level above 60 per cent at an average of at least 5 per cent per year. The structural deficit rule – called the “balanced budget rule” – must be incorporated into the national law of signatory states under the Fiscal Compact. An “automatic correction mechanism”, which is to be established at member state level and kicks in when “significant deviation” from the balanced budget rule is observed, must also be incorporated into national law.

Of all the member states who signed the intergovernmental treaty, only the Irish state put the Fiscal Compact to a referendum. The Fiscal Compact Treaty was adopted by just over 60 per cent of the voting electorate, with around 50 per cent turnout. The Fine Gael/Labour government’s decision to hold a referendum was not based on a belief in the right of the Irish people to have their say on their economic future, but rather their desire to go one step beyond simply incorporating the permanent austerity rules into legislation, and to insert them into the Constitution – despite the fact that the government’s Fiscal Advisory Council recommended the legislation option. Fine Gael, Fianna Fáil and Labour representatives urged the people to vote yes, dangling the carrot of access to the new bailout fund. The vote in favour was hailed by the government as an endorsement of its austerity policies.

The reality is that the Irish electorate was blackmailed into voting in favour of a proposal that endorsed a damaging austerity framework based on free-market fundamentalism as a result of the threat of crisis funds being withheld in future, and by the promise of the debt burden being relieved through the direct recapitalisation of the failed Irish banks by the future European Stability Mechanism. And after the approval of the Fiscal Compact Treaty and the constitutionalisation of austerity in Ireland, the Fine Gael-led government quietly dropped its call for the EU to recapitalise the Irish banks. Unbelievably, by 2015, the same Irish government representatives who had urged voters to approve the Fiscal Compact Treaty were pleading with EU authorities for more flexibility for Ireland’s implementation of the rules.

Irvin points out that Germany’s debt-brake cannot be good for other Eurozone countries, or even possible, for three reasons – that Germany’s exports to the Eurozone are by definition another member state’s imports; that there is insufficient global demand to sustain all Eurozone economies becoming net exporters like Germany; and that the public debt-brake completely ignores the problem of private debt, especially in the over-leveraged banking sector.

In a scathing critique of the Fiscal Compact, Francesco Saraceno and Gustavo Piga highlight that “no other country in the world has ever considered [such a rule], and with good reason” and say that the adoption of the Fiscal Compact has been “untimely, unfortunate and unequivocally wrong”. “Its uniquely negative effects, as the experience of Italy clearly shows, lie in the perverse features whereby, even if a government is allowed to renege year after year on the promised path toward a balanced budget, it is still required, every year, to recommit to a medium term (3-4 years) adjustment toward that balance. In so doing, business expectations are negatively affected, private investment plans are postponed, and stagnation becomes a permanent feature of the economy,” they write.

Return fiscal powers to member states

There have been repeated efforts, led by Germany, to exercise control over the budgets of member states. For several decades now, France’s demand for a European monetary union was always met with the German response that it must be accompanied by fiscal union, or German-led surveillance and control over national budgets. The same argument continues today, based on the same flawed ideology.

There have been several important proposals to reform the Fiscal Compact – for example, to focus only on the structural deficit; or to exclude capital investment from the rules. But while these proposals may loosen the straitjacket a little, it would be better to just take it off. As part of the Fiscal Compact treaty, the Council is required to adopt a formal decision on the Fiscal Compact by 1 January 2018 on whether or not to insert it into the EU Treaty. Saraceno and Piga argue: “If a number of important countries were to veto that move, this could set in motion a profound rethink of the appropriate fiscal policy infrastructure supporting the euro zone in future, one consistent with recent developments in macroeconomics.”

The Fiscal Compact has already been proven to be unworkable. The European Council voted last year to adopt the Commission’s recommendation to impose no fines for excessive deficits on Spain and Portugal in a clearly politically motivated decision. The austerity lie is losing its power, with even the IMF and the Commission questioning its benefits after a decade of stagnation. Barry Eichengreen and Charles Wyplosz argue that the attempt to centralise fiscal policy at the EU level is “doomed” and should be abandoned. In a paper on minimum conditions for the survival of the Eurozone, they write: “The fiction that fiscal policy can be centralised should be abandoned, and the Eurozone should acknowledge that, having forsaken national monetary policies, national control of fiscal policy is all the more important for stabilisation.”