MONETARY POLICY is a key tool for governments to use to benefit citizens, societies and economies. Central banks are empowered to determine interest rates, and to influence the exchange rate of their currency (and others’) by buying and selling reserves of foreign currencies. If a central bank sets a higher interest rate, this makes the return on this currency higher, leading to a higher demand for the currency and a resulting higher exchange rate. By lowering interest rates central banks can stimulate growth by expanding credit. With the creation of the ECB in 1998, members of the common currency transferred their power to set interest rates and other monetary policy powers to the ECB, which would set a centralised monetary policy across the Eurozone. The ECB and national central banks form the European System of Central Banks (ESCB), and the ECB can “exceptionally” provide emergency liquidity assistance (ELA) as a last resort for struggling Eurozone banks. The ECB differs from most of the other major central banks around the world in that it has a more limited mandate, and in its governance structure.

A narrow mandate

The neoliberal ideas, and the German economic ideology of ‘Ordoliberalismus’, that shaped the construction of the Eurozone can also be seen starkly in the nature of the ECB. This ideology has been dominant in Germany since the Second World War and combines a belief in a welfare safety net with the view that one of the government’s key roles is to promote market competition, stressing the importance of constitutional rules, as opposed to the use of discretionary policy. This ideology shaped the nature of the Bundesbank, which was dedicated to tightly controlling the money supply to maintain price stability. The ECB was constructed on this model, with a mandate to focus on price stability – controlling inflation. Despite the total discrediting of this ideology in the wake of the financial crisis, Berlin’s belief that if the government ensures inflation is kept low and stable, then markets will ensure growth and employment of their own accord, persists.

The ECB’s mandate is in contrast to many other major central banks, like the Federal Reserve in the US, which are tasked with the broader role of maintaining full employment and promoting growth, in addition to maintaining price stability. As a result of its narrow mandate the ECB only focuses on controlling inflation, regardless of how high the unemployment rate is. If there is low and stable inflation in the Eurozone as a whole – and in Germany in particular – then the ECB will ignore the growth needs of states experiencing high employment. In the midst of the recession and the sovereign debt crisis in 2011, the ECB actually raised interest rates twice, in April and July, contributing to the cause of the Eurozone’s double-dip recession. This caused major hardship in the crisis countries, particularly for mortgage-holders who were pushed further into arrears.

The other key difference between the ECB and other major central banks is its level of democratic accountability: for example, while the Fed is often described as “independent”, it is ultimately accountable to Congress. The ECB is unaccountable to any elected government or parliament. This feature reflects the drive by elites to “depoliticise” economic policy by outsourcing it to supposedly independent technocrats in order to weaken resistance to highly political decisions that have profound redistributive consequences for society. Bill Mitchell and Thomas Fazi write: “[T]he creation of self-imposed ‘external constraints’ allowed national politicians to reduce the political costs of the neoliberal transition – which clearly involved unpopular policies – by ‘scapegoating’ institutionalised rules and ‘independent’ or international institutions, which in turn were presented as an inevitable outcome of the new, harsh realities of globalisation, thus insulating macroeconomic policies from popular contestation”.

The decisions that the ECB has taken in response to the crisis have been extremely political, such as its decision to raise interest rates in 2008 and 2011, when the real danger to the majority of Eurozone members was deflation. The two most strikingly political acts during the crisis were the ECB’s threat to cut off emergency liquidity assistance to the Irish state unless it agreed to request a bailout, and its decision to cut off emergency liquidity to Greek banks in the middle of 2015 in a threat to Syriza that Greece would be forced out of the Eurozone if it did not submit to the conditions of the Troika that were resoundingly rejected by Greek voters in a referendum. The ability to withhold credit to elected governments gives the unaccountable ECB an enormous degree of power to impose its own policy on countries in need of assistance.

The ECB’s financing operations

In 2011 the ECB began the first of several financing operations in order to assist the economic recovery in the Eurozone. In December 2011 it announced its long-term refinancing operation (LTRO), which provided one trillion euro in credit in secured funding to troubled banks at a rate of one per cent interest. The banks often invested it into government bonds at higher rates, which helped the banks’ balance sheets but cost government budgets in debt servicing payments, and tied the banks and sovereigns even closer together.

As the Eurozone teetered on the brink of fragmenting in July 2012, ECB President Mario Draghi made his famed speech that is widely believed to have “saved” the common currency, which included the statement that, “Within our mandate, the ECB is ready to do whatever it takes to preserve the euro. And believe me, it will be enough”. The speech preceded a new financing operation called Outright Monetary Transactions (OMT) in which the ECB offered to purchase sovereign bonds of the most indebted states. In 2014 Paul Krugman described the OMT programme as a “bluff” because “nobody knows what would happen if OMT were actually required”. The OMT programme has not in fact ever been used, because no member state has met all of the requirements needed to activate it. Martin Wolf and others have observed that the bluff was so successful not only due to its announcement, but also due to the tacit acceptance of the announcement by all member states including Germany, as this was perceived by markets as a signal that the risk of the Eurozone disintegrating was eliminated. But he adds that while the spreads between government bonds in crisis and core countries fell sharply in response to the OMT announcement, they remain significant. “For countries caught in a deflationary trap, these spreads might yet prove unmanageable.”

In a telling side note, it was revealed in October 2017 that the Eurosystem had made super-profits of €6.2 billion between 2012 and 2016 from Greek bonds the ECB had purchased at knock-down prices in 2012. While the Greek government and its creditors in 2012 had agreed to “haircut” Greek bonds, those purchased by the Eurosystem were conveniently excluded.

Neither the LTRO nor the OMT programmes did much to actually improve the supply of credit to the productive economy. The next financing operation was announced in 2014 – targeted longer-term refinancing operations (TLTRO) – and it was aimed at providing banks with funds on the condition that they would be used to supply credit to small and medium enterprises as opposed to being directed towards speculation. But the lack of demand in the economy has meant that the TLTRO offer was not widely taken up by firms. Despite the ultra-low and at times negative interest rates, and the billions of euros handed over to banks through its financing operations, the ECB was not able to generate recovery in the real economy and restore growth, and it has persistently missed its target of 2 per cent inflation.

In March 2015, the ECB announced a quantitative easing (QE) programme in which it would create €60 billion each month and use it to purchase corporate sector assets and government bonds. It was originally intended to last for one year but has been extended and remains in place, though economists expect the announcement of “tapering” in the near future, the phased winding-down of the programme. The Corporate Securities Purchasing Programme (CSPP), introduced in March 2016 and now valued at around €125 billion, has been widely criticised by NGOs and MEPs for the lack of transparency on how the bonds are selected, and the fact that the funds are being directed towards multinational corporations and the fossil fuel industry. Corporate Europe Observatory has examined the limited publicly available data on the bonds favoured by the CSPP and found a marked preference for climate-damaging corporations. Another report by Corporate Europe Observatory published in October 2017 found that 98 per cent of all advisors in the ECB’s advisory groups have been assigned to representatives of the finance industry. Just three financial institutions, Deutsche Bank, BNP Paribas and Citigroup, occupied 208 out of 517 total advisory seats.

The QE for People and Positive Money campaigns have developed a detailed critique of the limited impact on real economic recovery of the ECB’s “trickle-down” QE programme and have developed excellent policy alternatives. This campaign is supported by dozens of leading economists. Two examples of alternative monetary policies they propose are for the ECB to transfer newly created money to Eurozone governments directly, who can use it to increase public spending on green infrastructure and services; or for the ECB to create money that can be directly distributed to citizens of the Eurozone, which would increase their purchasing power and directly enter the real economy. The current QE programme is not only unfair and ineffective – it is also increasing financial volatility and encouraging the inflation of new speculative bubbles.

A new banking crisis?

Despite the fact that the European banking sector has received more than €1.6 trillion through taxpayer-funded bailouts since 2008 – and despite the fact that the ECB has pumped in €60-€80 billion each month through its financing operations since March 2015 amounting to an additional €2 trillion in support – another crisis is unfolding in the European banking sector.

Banks in the EU, and particularly in the Eurozone, have been experiencing a chronically low level of profitability since the global financial crisis. While profitability of US and British banks has improved somewhat post-crisis, many Eurozone banks are struggling to keep their heads above water.

ECB Vice President Vítor Constâncio noted in a speech in Brussels in February that the key measure of profitability – return on equity – for euro-area banks “has hovered at around 5 per cent”, a rate which, he pointed out, “does not cover the estimated cost of equity”. By contrast, the return on equity in the US has recovered to above 9 per cent (around the current cost of equity in the euro area banks), and the industry generally considers 10 per cent to be a good rate of return. European banks’ income from interest, which was on average 19 per cent of their equity in June 2016, is less than their operating expenses of 20.9 per cent, according to the European Banking Authority (EBA).

The crisis has been demonstrated in the failure (or near-failure) of several banks across the Eurozone this year – including Italy’s Monte dei Paschi di Siena (MPS), Veneto Banca and Banca Popolare di Vicenza, and Spain’s Banco Popular – as well as the serious ill-health of German giant Deutsche Bank. Other banks that have caused concern, largely due to the results of the 2016 banking stress tests carried out on 51 major EU banks under the authority of the EBA, include RBS, which was bailed out by the British government in 2008 in the world’s largest ever bailout, and has since posted nine straight years of losses. Irish banks Allied Irish Bank and Bank of Ireland, British bank Barclays, Switzerland’s Credit Suisse and Austrian bank Raiffeisen are all also subject to concerns about their health and viability.

In an illustration of the seriousness of the systemic risk posed by the profitability crisis, EBA chairperson Andrea Enria said last October: “The problem is European in scale: we have more than €1 trillion of gross non-performing loans in the system; even considering provisions [money set aside to cover losses], the stock of uncovered non-performing loans is at almost €600 billion — more than all the capital banks raised since 2011, more than six times the annual profits of the EU banking sector, more than twice the flow of new loans.

“For supervisors, this casts serious doubts on the long term viability of significant segments of the banking system [my emphasis]. The same concern is shared by investors and is reflected in the low valuations registered in stock markets.”

Most experts and financial commentators point to four key contributing factors to this lack of profitability – the high volume of non-performing loans on the banks’ books (loans that are in default after 90 days of non-repayment); the very low interest rate environment arising from the ECB’s recent monetary policy; the fines for misconduct banks have been required to pay since the crisis; and over-capacity in the sector, including increasing competition from FinTech.

Between 2010 and 2014, EU banks paid out around €50 billion in settlements and fines imposed by regulators for misconduct, largely due to mis-selling the risky financial products that contributed to the global crash. The EU’s largest banks, those classified as global systemically important banks (G-SIBs), were the worst culprits and paid the vast majority of the €50 billion figure. A report by the European Systemic Risk Board in 2015 found that past and looming fines would wipe out erase basically all of the new capital that had been raised by European G-SIBs over the past five years.

While misconduct fines and over-capacity dampen profits, the two most important of the four factors listed above are the NPL problem and the interest rate environment. But a key pressure on profitability that the ECB, EBA and the other EU institutions routinely fail to acknowledge is on the demand side – ie, the general economic stagnation in the Eurozone that has caused the demand for credit to fall and remain low. This stagnation has also contributed to and worsened the NPL problem. Euro-area banks held just over €1 trillion in NPLs last year, the equivalent of around 9 per cent of the Eurozone’s GDP, and amounting to around 6.4 per cent of total loans in the Eurozone. The level of NPLs differs dramatically across the euro area, with almost half bank loans in Greece and Cyprus now classified as NPLs, and Italy, Ireland, Portugal and Slovenia all holding NPLs at rates of 10-20 per cent.

There is a clear overlap between the high level of NPLs and the impact of the financial crisis on the so-called peripheral economies in the Eurozone, and a clear interaction between the austerity measures prescribed for these economies by the Troika and their inability to significantly reduce their NPL ratios. The collapse of the industrial sector in Greece and Italy in particular has been a major contributing factor to the rise of distressed loans as businesses of all sizes failed and their owners were unable to repay loans. The austerity policies enforced by the Troika in the crisis countries in return for bailout funds inevitably exacerbated the NPL problem.

Publicly funded bank bailouts are back with a vengeance

“EU forges bank bailout deal to protect taxpayers” – that was the Associated Press headline in June 2013, describing the agreement reached in Brussels on the EU Banking Union. The Banking Union is an initiative to further integrate the banking and financial sectors in the Eurozone countries, which was promoted as a response to the global financial crisis and subsequent sovereign debt crisis. It is envisioned as having three pillars based on a “single rulebook” – a system of harmonised supervision under the Single Supervisory Mechanism; a single resolution mechanism and associated fund implemented by the Bank Recovery and Resolution Directive (BRRD) at the beginning of 2016; and an as-yet to be developed third pillar of a European Deposit Insurance Scheme.

The Banking Union, European lawmakers assured the public, would call time on the “too-big-to-fail” problem and ensure taxpayer-funded bailouts – which had cost EU governments more than €1.5 trillion since 2008, including €64 billion in the Irish state – were a thing of the past. The BRRD was supposed to make sure that in case of a bank failure, the institution would be wound down in an orderly way by an early intervention by regulators, and that senior bondholders and depositors with more than €100,000 in the bank would be “bailed in”. Creditors would have to incur losses of at least 8 per cent of their liabilities before a bank would be able to receive government aid. Speaking to reporters at the summit where the deal was reached between EU Finance Ministers that day in 2013, then-Irish Finance Minister Michael Noonan said: “Bail-in is now the rule… This is a revolutionary change in the way banks are treated.” But there was an exception clause, as there usually is in EU legislation, and its name was “precautionary recapitalisation”.

Resolution Directive fails miserably in its first test

The Italian banking crisis that deepened throughout 2016 culminated in the December announcement by the Italian government of a €20 billion taxpayer-funded rescue package for the ailing MPS and other Italian banks, indicating its intention to activate the precautionary recapitalisation clause of the BRRD. The clause allows for the bail-in of creditors to be sidestepped if certain conditions are met – namely that the bank is still solvent, and its resolution would threaten financial stability. This exceptional clause is complemented by a similar “safeguard” clause in the EU’s state aid legislation on burden-sharing.

After months of negotiations between the European Central Bank (ECB) and the Commission, about both the extent of the capital shortfall and the terms of the deal, Competition Commissioner Margrethe Vestager reached an agreement in principle with the Italian Finance Minister on June 1, 2017. The Commission, and the ECB in its supervisory role, gave the green light to the precautionary recapitalisation. “State aid in this context can only be granted as a precaution (to prepare for possible capital needs of a bank that would materialise if economic conditions were to worsen) and does not trigger resolution of the bank,” Vestager said in a statement.

Conditions of a precautionary recapitalisation include that broader financial stability must be threatened by the bank’s failure; the state support cannot be used to cover previous or near-term expected losses; and the need for state support must be only temporary. But MPS already received two state-funded bailouts in 2009 and 2012, casting significant doubt on whether it meets these two latter criteria.

Back in December when the Italian government made its rescue package announcement, the ECB suddenly began to say that MPS’s capital shortfall was not €5 billion as previously estimated but actually €8.8 billion. The ECB didn’t bother to explain publicly how it arrived at this figure, but its retroactive and opaque revision of the figures raised serious concerns and questions about the health of MPS. Was the bank actually solvent when it applied for a precautionary recapitalisation? If not, it would not qualify for public assistance. The details of the Commission’s agreement in principle have not yet been made public.

There are many criticisms that can be made of the resolution aspects of the Banking Union legislation. The bail-in of creditors of only 8 per cent is, in many cases, going to raise a totally insufficient proportion of the costs of a resolution. In ordinary insolvency procedures investors would usually lose far more than 8 per cent. Bail-in also poses additional risks to ordinary taxpayers in a number of ways including through increased premiums in pensions and health insurance, and through the mis-selling of risky and inappropriate financial products that are eligible for bail-in to small retail investors.

The precautionary recapitalisation clause, however, is the glaring loophole that makes a joke out of the Banking Union’s promise to end taxpayer-funded bailouts of banks and to resolve the ‘too-big-to-fail’ problem. Under the Bank Recovery and Resolution Directive, a review of the precautionary recapitalisation clause was supposed to have taken place by now. The Commission was required to review whether “there is a continuing need for allowing the support measures” in the clause by December 2015 and report on this to the European Parliament and Council, which it has failed to do.

Now, the European Banking Authority (EBA), supported by many within the European Central Bank (ECB), is making a concerted push for the precautionary recapitalisation loophole to be invoked in order to use public funds to bail out the big bank across the EU more generally, by calling for state funds to be used to reduce the high level of non-performing loans in European banks and to restore them to profitability.

A crisis of abundance

Writing in response to the Great Depression, Keynes said, “This is not a crisis of poverty, but a crisis of abundance,” a description that is perfectly fitting for the current economic crisis. The ongoing tendency towards stagnation in the Eurozone and in the broader economy is not primarily the result of trade imbalances, which in any case, have been reduced as a result of the fall in aggregate demand. There is an unprecedented mass of money not being used in the economy, which has built up over decades of a declining labour share of income and record-high corporate profits. There is at least US$5 trillion in “idle money”, much of it resting in tax havens. Varoufakis writes: “Try to imagine the mountain of cash on which corporations in the United States and Europe are sitting, too terrorized by the prospect of insufficient consumer demand to invest in the production of things that society needs.” He notes that every crisis generates two mountains: “one of debts and losses, another of idle, fearful savings” – the only difference being the scale of this crisis.

Investment continues to stall across the Eurozone, and the Juncker Investment Plan, and its key instrument, the European Fund for Strategic Investment (EFSI), has been a dismal failure. It was announced in late 2014 as an initiative from the Commission in partnership with the European Investment Bank (EIB) in order to address the ‘investment gap’ that the Commission estimates to be 200-300 billion euros per year in the EU. The stated goal of the Juncker Plan was to “mobilise” more than €300 billion in private capital investments – by creating an initial fund of just €21 billion to secure loans for infrastructure projects. The European Trade Union Confederation immediately responded to the Juncker Plan by saying the Commission was “relying on a financial miracle like the loaves and fishes”.

There was no new money forming the EFSI – the seed capital was cut from other existing EU budgetary programmes, including the research plan Horizon 2020 and the Connecting Europe transport infrastructure programme. This €21 billion in initial capital was to be used to guarantee €60 billion of EIB borrowing to fund riskier projects than the EIB usually funds. The entire rationale of the Juncker Plan was to ensure that private investment that would otherwise not have happened took place. The investment plan stipulates that the funds must be disbursed across all EU economies according to the size of their GDP levels, meaning most of the projects that have been approved have benefited Germany and Britain instead of the smaller peripheral economies who are in greater need due to the fact that investment has largely ground to a halt. It has largely focused on public-private partnerships, which are being used across the EU to promote privatisation of public goods and services.

The Bruegel think-tank undertook a study of the first 55 EFSI-funded projects that were approved in the first year, and found that 42 would in all likelihood have proceeded anyway in the absence of the Juncker Plan. The only difference is that public money is now being used as a guarantee for private ventures.

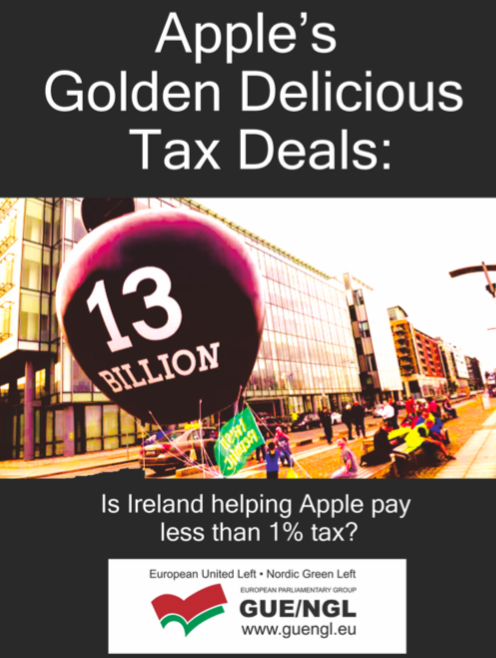

The European Parliament admits the results of the Juncker Plan have been disappointing and that it has failed to unleash any discernible surge in investment. The most critical group, the European United Left (GUE/NGL) points out that most of the investments made under the plan would have proceeded regardless, without the EU guarantee, but now private investors can shift the risk of their investments to taxpayers. The group argues, “The EFSI induces rent seeking and asset stripping by private investors at the expense of the Union budget, via public private partnerships, the privatization of profits and the socialization of losses, while only sparely contributing to additional investment”.

This is an excerpt from the economic discussion document launched by MEP Matt Carthy on October 27, entitled The Future of the Eurozone. Download the full document for a referenced version of Chapter Six, above.