Below is an outline and summary of a new report I co-authored with Danish researcher Martin Brehm Christensen (University of Copenhagen), which examines Apple’s post 2014 Irish restructure, the effective tax rate it pays today as a result, and the role of the Irish government in facilitating industrial-scale tax avoidance by Apple and other multinationals. The report was commissioned by GUE/NGL and was launched on 21 June 2018 in the European Parliament in Brussels.

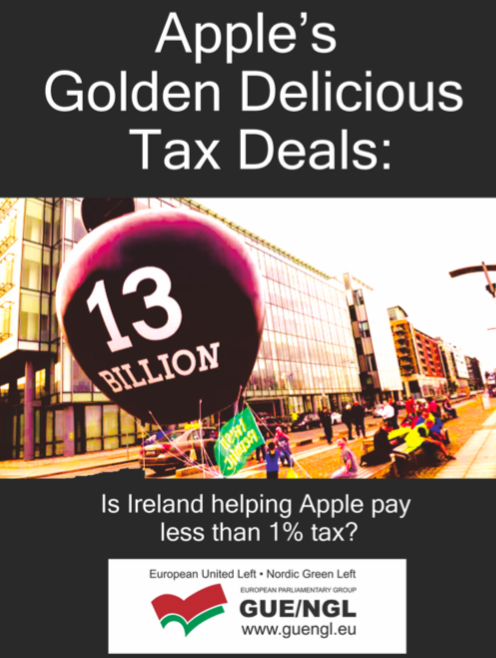

Apple’s Golden Delicious tax deals: Is Ireland helping Apple pay less than 1% tax?

Download the full report here: Apple tax structure and rate post-2014

This report was commissioned by GUE/NGL members of the European Parliament’s TAX3 special committee on tax evasion, tax avoidance and money laundering. It examines the corporate tax rate paid by Apple globally and in the European Union (EU) over the period 2015-2017, after it made significant changes to its corporate structure in 2015.

These changes were made in response to the United States (US) Senate Subcommittee on Investigations examination of Apple’s tax affairs in 2013, the European Commission’s 2014 investigation into state aid provided by Ireland to Apple, and the changes to Irish tax residence law ending the ability of companies to be “stateless” for tax purposes.

In addition to estimating the effective corporate tax rate Apple has paid from 2015-2017, this report also examines the nature of Apple’s 2015 corporate restructure, and the methods it uses to continue to avoid paying tax today. Lastly, it examines the features of Irish tax law and policy that facilitate Apple’s ongoing tax avoidance.

Tax rate in the European Union and globally 2015-2017

1) Apple may have paid as little as 0.7% tax in the European Union (EU) from 2015-2017.

2) Using data from Apple Inc’s 10-K filings to the US Securities and Exchange Commission, we estimate that as a result of the new Irish structure, and Apple’s broader global tax structure, Apple’s tax rate for the period 2015-2017 for its non-US earnings is between 3.7% and 6.2%.

3) Two alternative calculations of the average rate paid on non-US earnings reach similar results, of between 4.5% and 6.7%, and between 4.7% and 6.9%.

4) Using data from Apple Inc’s 10-K filings to the US Securities and Exchange Commission we estimate that Apple is paid corporate tax at a rate of between 1.7% and 8.8% in the European Union during the period 2015-2017. This estimate assumes that Apple’s provisions for foreign tax equals money actually transferred to foreign governments.

5) If we assume the highly likely scenario that Apple’s provisions for foreign tax is substantially smaller than the amount actually transferred to foreign governments, we estimate that Apple may have paid as little as 0.7% tax in the EU from 2015-2017.

6) Applying the range of estimated tax rates paid in the EU from 2015-2017, we estimate that Apple has avoided paying between €4 billion and €21 billion in tax to EU tax collection agencies from 2015-2017.

Apple’s Irish restructure in 2015

7) Apple’s new European tax structure remains shrouded in secrecy, partially due to a lack of financial transparency in Ireland and Jersey. Most of its financial information remains secret globally.

8) Apple continues to use Ireland as the centrepiece of its tax avoidance strategy. Following the US Senate inquiry (2012-2013) and the initiation of the European Commission’s state aid investigation into Ireland (2014), Apple organised a new structure in 2015 that included:

- The relocation of its non-US sales from ‘nowhere’ to Ireland;

- The relocation of much of its intellectual property from ‘nowhere’ to Ireland;

- The relocation of its overseas cash to Jersey.

9) As well as relying on the information revealed in the Paradise Papers and Apple’s statement responding to these revelations, this restructure can be observed in the macro-economic data of Ireland from 2014-2018, particularly in the first quarter of 2015. Major changes occurred in Ireland’s GNP, GDP, exports, imports, investment, external debt and more. Despite the relocation of sales income and intellectual property to Ireland, there was no observable corresponding increase in corporation tax received from Apple by Irish Revenue.

10) With the assistance of the Irish government, Apple has successfully created a structure that has allowed it to gain a tax write-off against almost all of its non-US sales profits.

Apple is achieving this by:

- Using a capital allowance for depreciation of intangible assets at a rate of 100% (this rate will be capped at 80% from 2017, but the cap will not apply to the intangible assets brought onshore from 2015-2016, which can still benefit from the 100% rate);

- A massive outflow of capital from its Ireland-based subsidiaries to its Jersey-based subsidiaries in the form of expenditure on IP and debt;

- Using interest deductions of 100% on this intra-group debt;

11) The Irish government introduced the 100% rate on capital allowances for intellectual property (IP) following a recommendation made by the American Chamber of Commerce in Ireland in 2014.

12) The law governing the use of capital allowances for IP is not subject to Ireland’s transfer pricing legislation, but it includes a prohibition from being used for tax avoidance purposes. Apple is potentially breaking Irish law by its restructure and it exploitation of the capital allowance regime for tax purposes. If the same legal reasoning used in the European Commission’s state aid ruling on Apple and Ireland is applied, Apple is in breach of Irish tax law, and owes Irish Revenue at least 2.5 billion additional euros in unpaid tax annually from the period 2015-2017.

13) The use of this structure has contributed to a significant increase in the amount of cash Apple is sitting on in offshore tax havens.

Features of Irish tax law that enable Apple’s tax avoidance

14) Apple is unlikely to be the only multinational corporation using this structure, which is advertised as a typical structure used by large corporations involved in trading in intellectual property by corporate law firms. We have called it the “Green Jersey” in reference to the use of the Jersey-based subsidiary by Apple, though it is not strictly necessary to use an offshore tax haven as Apple has.

15) The essential features of the Green Jersey scheme are:

- It can be used by large multinational corporations engaged in trading IP;

- It has specifically been designed by the Irish government to facilitate near-total tax avoidance by the same companies who were using the Double Irish tax avoidance scheme;

- While the Double Irish was characterised by the flow of outbound royalty payments from Ireland to Irish-registered but offshore tax-resident subsidiaries, this scheme is characterised by the onshoring of IP and sales profits to Ireland;

- Sales profits are booked in Ireland, but the expenditure the company incurs in the once-off purchase of the IP license(s) can be written off against the sales profits for years by using the capital allowance programme for intangible assets;

- It is beneficial for the company to complement the tax write-off by continuing to use an offshore subsidiary, but not for outbound royalty payments to flow to. The role of the offshore subsidiary is to store cash and provide loans to the Irish subsidiary to fund the purchase of the IP. The expenditure on the IP is written off, but so too are the associated interest payments made to the offshore subsidiary, which thus accumulates more cash that goes untaxed.

16) Many of the features of Irish tax law that were identified as factors facilitating tax avoidance in the Commission’s state aid ruling remain partially or fully in place in Ireland. Despite the announced phase-out of the Double Irish scheme, we have found that the “management and control” provision allowing the creation of Double Irish structures remains in place through several of Ireland’s tax treaties, including treaties with states considered to be tax havens.

17) Several other key features of Ireland’s tax regime that were criticised in the context of the Apple state aid ruling, and which remain fully or partially in place, include:

- Ireland’s intellectual property tax regime including R&D credits that are open to abuse, and the lack of withholding taxes on outbound patent royalty payments;

- The use of private “unlimited liability company” (ULC) status, which exempts companies from filing financial reports publicly. The fact that Apple, Google and many others continue to keep their Irish financial information secret is due to a failure by the Irish government to implement the 2013 EU Accounting Directive, which would require full public financial statements, until 2017, and even then retaining an exemption from financial reporting for certain holding companies until 2022;

- Ireland’s one-way transfer pricing laws that examine only the Irish-resident party involved in a transaction;

- Continued use of Advanced Pricing Agreements and Revenue “opinions”, which may not be subject to the same requirements on mandatory automatic exchange of information between EU member states under the third EU Directive on Administrative Cooperation.

Download the full report here: Apple tax structure and rate post-2014